William Henry Lewis has a list of firsts both on and off the college football field. Lewis’ greatest contribution to the game might be the simplest.

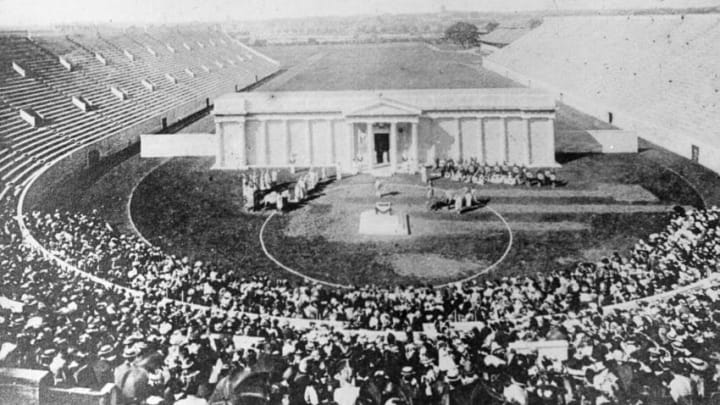

During college football’s infancy, the game bore little resemblance to what it is now. The ball was round, and players kicked to score. There was no such thing as a shotgun or even a huddle. Most of the football powers resided in the Ivy Leagues and the game was seen as a way for young men to expend energy after the Civil War ended. During this time, Yale, Brown, Princeton and Harvard.

One of Harvard’s better players was a 175-pound law student named William Henry Lewis. In 1892 and 1893, Lewis was the first African-American named an All-American by sportswriter Casper Whitney. When Lewis finished at Harvard, the former center decided to coach instead of pursuing law school. That decision benefitted both Harvard and Lewis. During Lewis’ 11-year coaching career, the Crimson compiled a 114-15 record which included an undefeated season in 1898.

During that time, Lewis would author a book on football A Primer of College Football in 1896 and football pioneer Walter Camp had Lewis contribute a chapter to his annual publication Spalding’s How to Play Football. Though Lewis was an integral part of the coaching staff during his time at Harvard, and one of the few assistants compensated, the former All-American was never promoted to head coach.

Eventually, the law would call Lewis away from coaching. In 1903, president Theodore Roosevelt would appoint Lewis US attorney for Boston, and then elevating Lewis to US assistant attorney for Immigration and Naturalization for New England states in 1907. President William Howard Taft would make Lewis the first African-American assistant US attorney.

Before Lewis left coaching, he would leave a lasting mark on the game. In 1905, Harvard administrators voted to ban football. It was Lewis and several Harvard alumni that developed rules that made the game safer. Lewis would suggest a line of demarcation that separated the offense from the defense. Instead of allowing teams to crowd the line of scrimmage, Lewis suggested separating the offense and defense by the length of the ball.

Players could not cross this “zone” until the ball is snapped. This came to be known as the Neutral Zone. Something part of the game to this day.