This marked the fifth season of college football’s existence. The cast of characters scaled back from the year before, but the history remains deep.

The 1874 college football season is something of a riddle, broken up into segments that are sometimes included with the year before and sometimes with the year after. There was spring football, there was fall football, and without any oversight or even uniform rules it was pure anarchy — a sport negotiated between those actually playing the games.

Once rules were settled to everyone’s satisfaction, the players did battle before crowds who gathered to watch the curiosity. Stadiums were nonexistent, teams finding a flat patch of grass and spectators lining the perimeter wherever space was available. The sport was still years removed from becoming a big-money spectacle, and at this point spectatorship was accessible to anyone who could manage their way to the field.

Football’s brief foray into the south proved a one-off affair. The 1873 showdown between next-door neighbors Washington and Lee University and Virginia Military Institute inspired no follow-up on their respective schedules, and football remained an in-house affair despite the proximity of the two institutions. It would take another decade and a half before intercollegiate football competition returned to the former Confederacy.

There were still eight teams in action during the course of 1874, including one from the Great White North. Let’s dive in and take an irreverent look at how things transpired in the first season where Princeton was not recognized officially as a national champion by the NCAA.

Springtime football: McGill visits Harvard in May 1874

Often included in the statistics for the 1873 season is the pair of games played by Harvard and McGill in 1874. Harvard shied away from playing its American counterparts throughout the 1873 season, unwilling to sacrifice or even just alter their local football code in the interest of popularizing the American sport. When the Canadians came calling in April 1874, however, there was little hesitation at accepting the offer.

The schools opted to play two games, the first by Harvard’s rules and the latter under a version of rugby rules popular among the McGill students. Squaring off on May 14, Harvard had little trouble knocking off their Canadian counterparts 3-0 playing their own style. The following day, McGill had the upper hand as the two teams returned to the field in Cambridge to play under the rugby-style code.

That required the installation of new equipment, the rugby goalposts differing from what Harvard already had on campus.

Apparently Harvard protested too much the previous autumn when Yale, Princeton, Rutgers, and Columbia tried to bring them into the fold to reconcile the rules of the American game. The lads from Massachusetts apparently loved the Quebecer pastime, readily adopting it for themselves.

The first rugby match ever played in the United States ultimately ended in a draw…

The two teams did play again some future day, specifically later in 1874. Making a trek across the border to Montreal, Harvard took on McGill again in a rubber match under the same rugby rules. In front of 2,000 spectators at the Montreal Cricket Grounds, the third battle transpired.

Officially the teams played to a scoreless draw under the scoring system of the period. Harvard, however, walked away boasting superiority on the pitch after scoring three tries (referred to in the newspaper clipping below as “touch-downs”) and holding McGill without any positive gains in the first road game in school history.

What appeared to be a budding rivalry between the two schools on either side of the international border turned into a strange little anomaly in college football history. The introduction of more rugby elements to college football had a massive, irreversible effect on how the American game developed.

It did not, however, result in more international competitions between Canadian and American schools and — once finally reconciled with the versions of football at other universities — created a new sport that did not translate to competitions with schools like Eton College.

Football as it was played by other universities in 1874

As influential as those two Harvard-McGill games and their October followup proved to be for the long-term development of college football, they really didn’t mean jack squat in 1874 for the mythical national championship race. As it had for the past several years, the pecking order came down to Princeton and Yale.

This time, however, beating Rutgers did not prove enough to snatch away the national title.

Which team would you prefer?

TEAM A

- 2-0 record

- average score = 6-0

- opponent win pct. = .250

TEAM B

- 3-0 record

- average score = 6-1

- opponent win pct. = .571

For the second time in the previous three seasons, Princeton and Yale ducked one another on the field. That left it to the retroactive selectors to sort out significance from their wins over common opponent Columbia and their overall strength of schedule.

Princeton played two games in 1874, beating both Columbia and Rutgers by identical 6-0 score lines. Columbia finished the year 1-5, Rutgers 1-3. Taking out Princeton’s games against those two teams, and the Tigers played opponents with a combined .250 winning percentage (2-6).

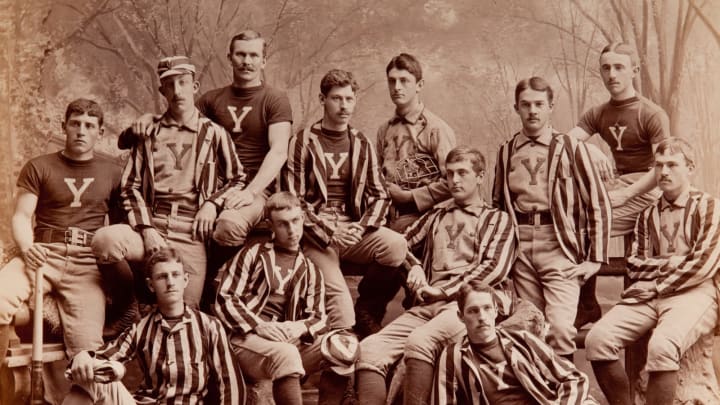

Yale shut out a strong Stevens Tech in their season opener before toppling Columbia twice by 5-1 and 6-1 scores. Other than their loss to Yale, Stevens Tech was a perfect 3-0 over the rest of the season; when combined with Columbia’s 1-3 record against teams not named Yale, the Bulldogs played opponents with a combined .571 winning percentage (4-3).

It was quite the understatement when newspapers reported after the Bulldogs’ first win over Columbia, “Football is becoming quite popular at Yale.”

For the first time in school history, Yale was able to claim a national championship for themselves. Now they would find, as Princeton had before them, that the real difficulty was in maintaining that standard of championship football across multiple seasons. Unlike Princeton, Yale would not have the advantage of earning four of their national titles before anyone else really played the sport yet.

The changing tides of college football in the 1870s

A sport that originated as a version of soccer quickly evolved elements that would start to become familiar to college football fans in the 21st century. Harvard, a latecomer to intercollegiate competition among the biggest programs of the 19th century, led the way in this regard.

Thanks in part to their obstinance about maintaining the Boston rules by which they played, the Crimson opened the door for the Canadians to influence the future development of the American game. That influence would continue into 1875 and beyond, again at Harvard’s lead.

Dominating one’s anomalous pastime is one thing, however. Far different is beating all comers at a mutually agreed-upon style of play, as Yale pulled off in 1874 to secure the national title and Princeton did to earn Parke Davis’s nod as a co-champion.

The NCAA tabs the Bulldogs alone, though, killing Princeton’s streak atop the sport since its inception. Fans of the “Ain’t Played Nobody” school of argumentation shed no tears for the Tigers.