Football expanded, rules changed, and yet so many things remained the same in 1881. Here’s another irreverent look back at college football history.

The 1881 season was marked by the rise of even more college football programs, as the total number of teams participating boomed to 20 programs. Scattered mostly through the northeastern states, the sport also continued to plant roots into the Midwest and deeper into the south.

With so many new teams, there were also a grip of lopsided scores. All but six games over the course of the fall resulted in both teams putting points on the scoreboard. For that matter, despite the best efforts of the committee of top football-playing universities to standardize scoring, every contest was still in some ways a negotiated settlement before a single second came off the clock. That resulted in some wildly divergent scores, with quarter- and half-points accruing in several games.

Ultimately, though, this season was in actuality another link in a chain of dominant efforts by the two hegemonic powers of the pastime. As much as Harvard tried to push Princeton and Yale in 1881, the Tigers and Bulldogs proved too much to handle even for the Crimson.

As things change in college football, so they stay the same. That dictum proved especially relevant in 1881, as the usual suspects clogged the top of the standings and a traditional Thanksgiving showdown once again offered little resolution.

Let’s dig into the archives and take an irreverent look back at the 1881 season.

The rise of October football as a commonplace occurrence

In its earliest years, football was exclusively a November sport. Beginning in 1873, the fourth season in college football history, the sport started to push up into the October calendar. At first it was only a handful of games per year — three in 1873 and 1874, five in 1875, two in 1876 and 1877, three in 1878 and 1879, and six in 1880. Once 1881 rolled around, though, the trend went from an occasional anomaly to an ordinary occurrence.

From October 15 through Halloween, the month featured a full dozen games. This included a trio of games between Harvard and Canadian squads, as the Crimson continued their historic trend of looking to the Great White North for opponents. Princeton knocked off Rutgers and Stevens Tech to claim Garden State supremacy yet again and also took out Penn in the first of two contests between the future Ivy League schools.

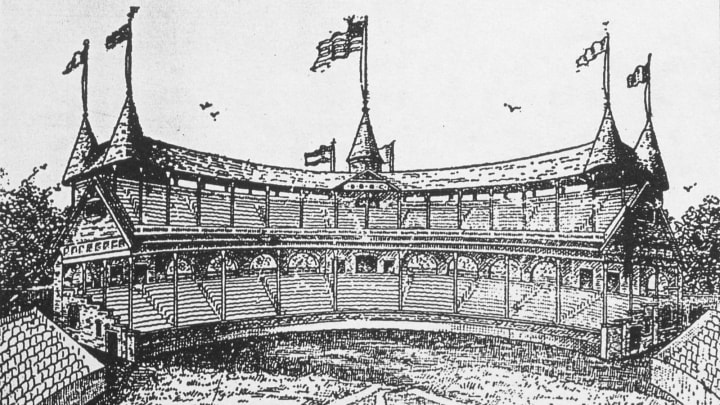

It also included the first road trip by Michigan to New England, as the Wolverines squad played a three-game barnstorming tour that began in Massachusetts where the Wolverines took on Harvard in a Halloween showdown at the South End Grounds in Boston.

Playing before a crowd at the 6,800-seat home of the Boston Braves, Michigan put in a valiant effort but was unable to keep Harvard out of the endzone. The record books notch this as a 4-0 Crimson victory, indicating based on the press of the time that touchdowns apparently counted for four points apiece.

That same day, Massachusetts trampled Wesleyan in a 36-0 rout. A survey of press records shows no indication of how scoring transpired in this contest where the final score looks suspiciously familiar to more modern results. Either way, football was most decidedly NOT “looking up at Wesleyan” in 1881.

Everything, and yet nothing at all, was settled in November

The landmark trip east by Michigan continued with a 2-0 loss to Yale at Hamilton Park in New Haven and concluded with a 1-0 defeat against Princeton in on the New Jersey campus. The Wolverines were simply smaller and less experienced than their counterparts, who were able to exert their will on the visitors.

Michigan would have its day in the sun soon enough, but 1881 was not destined to be their breakout year. Rather, merely making the voyage eastward proved that Michigan was in the football business to stay. As the first embedded anchor in Midwestern football, the Wolverines set an example that other teams in the region soon followed.

Also fascinating at this time was the continued presence of college football in Kentucky. A year earlier, the Centre Praying Colonels fell in back-to-back contests against Kentucky University (now Transylvania University) from Lexington. In 1881, while Centre stepped back and sat out the season, Kentucky U. was still on the field. A trio of games against cross-town rival Kentucky State College (now the University of Kentucky) set local supremacy, as Kentucky University won two of the three showdowns.

Penn State also played its first football game, taking down Lewisburg (now Bucknell University) in a 9-0 shutout. Dartmouth also launched its program in 1881, with a win and a tie in a pair of road games against Amherst.

Just as it had been for more than a decade by this point, however, the national championship remained the exclusively shared property of Yale and Princeton.

Princeton peeled off seven straight shutout victories to start the season. The Tigers took down Rutgers and Penn twice, routed Stevens Tech, secured victory against Michigan, and held their own in a win over Columbia. Harvard thwarted the opportunity to reach the Yale showdown undefeated and untied, as the Crimson hunkered down and forced Princeton to settle for a scoreless draw.

Yale, meanwhile, only played five games ahead of their annual Thanksgiving duel with Princeton. The Bulldogs toppled Amherst in their season opener before overcoming Michigan on the second day of November. Another dominant showing against Amherst and a pair of 1-0 wins over Harvard and Columbia put Yale in the driver’s seat of the national title race.

The Harvard game in particular is interesting in that it demonstrated the consequences of the new scoring rule for safeties. With the Crimson downed in their own endzone four times for safety, Yale earned victory by default over their rivals.

All Yale had to do now was pull out a victory against Princeton to secure an undisputed consensus national title. Given that the game ended in draws in each of the previous two years and three out of their last four meetings, victory was hardly a guarantee even for a team like the Bulldogs.

Indeed, the Elis were forced to share the national title yet again with their Princetonian rivals after another 0-0 result at the Polo Grounds in New York. That is true, at least in retrospect. When looking at contemporary sources, however, Yale was almost universally considered the champions of 1881 after finishing with a 5-0-1 mark versus a 7-0-2 finish for the Tigers.

Of course, the opinion that Yale was the national champion of 1881 was hardly universally accepted by either media members or fans of the game. The Bulldogs did not run through their schedule with a perfect record, and they were one of five teams to finish without a loss by the end of the season.

Penn State played only one game, limiting any consideration they might have received in the race, and Dartmouth’s one win and one tie were also not enough to tip the scales their way. Richmond, which brought football back below the Mason-Dixon Line with a pair of December victories over Randolph-Mason, was also too new to the scene to draw much attention.

Instead, the debate (as it had so many times before) came down to Yale and Princeton. The bulk of public support was on Yale’s side, but Princeton had its apologists as well.

In the end, the modern NCAA sides with Yale in the dispute. What this shows, however, is that absent a mechanism to guarantee a decisive result — and absent a team without losses or ties — there was no way to definitively crown a champion in any given season.

The beauty of college football’s second decade, ultimately, was that its rougher edges were filed down even as it retained some of that romantic rebelliousness that characterized its earliest years. As more schools came on board and rules slowly settled into place, the Wild West feel faded away a bit even as the sport remained an anarchic space of sorts. Out of that anarchy, Princeton and Yale were still waiting for a team that could push them consistently.