There was no question about the most dominant team in 1882, as only one swept through a multi-game college football schedule.

In the previous few seasons before 1882, college football worked to standardize the number of players per side as well as tweak its scoring system. Still, a lack of more substantive uniformity over the sport meant that some teams barnstormed through eight or more games while other programs only took on one intercollegiate test per season.

As such, flip through the record book and look at just about any 19th-century season and you’ll find a boatload of guesswork in terms of rating teams. Just about the only way to ensure that a team is a consensus national champion is if that team blows through its schedule with a perfect record — and no other team finds itself undefeated.

After years of gridlock against rival Princeton, Yale finally broke through and secured an undisputed title in 1882. The Bulldogs romped through eight games, winning them all and giving up only one point along the way.

If the 1870s were the decade of Princeton and the sport’s amorphous evolution, the 1880s were the Yale decade when college football started to take a viable shape and expand across the country. Let’s dig in deeper and take no prisoners with this irreverent look back at the 1882 college football season.

Was 1882 really another Manifest Destiny moment for college football?

Officially there were 25 colleges and universities that suited up and played football in 1882. That, however, doesn’t include the fact that often programs played not only other institutions of higher learning but also public and private athletic clubs, military base squads, and factory teams. At a time when football was still finding its footing among the American populace and universities were adopting the game in fits and spurts, finding competition meant having to get creative at times.

Even so, more colleges were embracing the sport — in one form or another —with each passing year. Football in Minnesota kicked off on September 29, when the Golden Gophers took down Hamline University of St. Paul in a 4-0 victory. Eighteen days later, Hamline leveled the score when they downed Minnesota 2-0.

Three months later, the game landed in the Rocky Mountains when Colorado College took on a team from the Sigafus Hose Company in Colorado Springs on Christmas Day. Unlike football in other parts of the country, both teams turned this into a relatively high-scoring affair that Colorado College ultimately won 10-8.

For the second straight year, Richmond proved itself the best team in Virginia after securing a 5-1 victory over Randolph-Macon. And football also continued its process of embedding in Maryland, as Johns Hopkins in Baltimore also formed a team despite protests of the university. Officially unaffiliated with the school, the “Clifton Athletic Club” lost to Baltimore Athletic Club in early October before following up with an 8-0 loss to Navy on the final day of November.

What this season reveals is a confusion around various forms of the game. In his look back at the 1882 season, scholar Melvin Smith sifted through past records and illustrated that what we consider college football today was really an admixture of three different codes. In Minnesota and Virginia they were playing some type of soccer. Colorado College was engaged in rugby along more traditionally British lines. In reality, the game we now know in an American sense was being played by only around 18 schools that year.

The northeast remained the epicenter for idiosyncratic American game

Another major development in 1882 was the increasing determination to distinguish the American game from the British versions of football. Once again, the Intercollegiate Football Association (comprised of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia) came together in October 1882 with the hopes of further concretizing their sport in a fashion that would make it even more popular as the dominant football code in the country.

Walter Camp, lionized as the “father of American football” to this day, was instrumental in these meetings since first attending as a player in 1878. Having recently finished his playing days at Yale the previous season, he represented his alma mater once again at the meeting in New York.

It was this season where down and distance really started to become a regular feature of the game, at least in the northeast, along with snapping the ball from a line of scrimmage (a concession Camp first lobbied for and won in 1880).

These dynamics were not entirely nailed down, as can clearly be seen in the manner in which Princeton debated the intricacies of these rules. While there was still room for tinkering with the sport, though, some of its foundational aspects were already starting to fall into place.

After originally taking to the Association version of the sport, American football quickly capitulated to Harvard’s early insistence on playing a modified version of their Boston rules with the rugby they learned over the years from Canadian opponents.

Once again, however, it was not to be Harvard’s year. Instead, Camp’s beloved Bulldogs snatched the throne as the kings of college football in 1882.

Yale’s perfect 1882 run stems streak of shared titles with Tigers

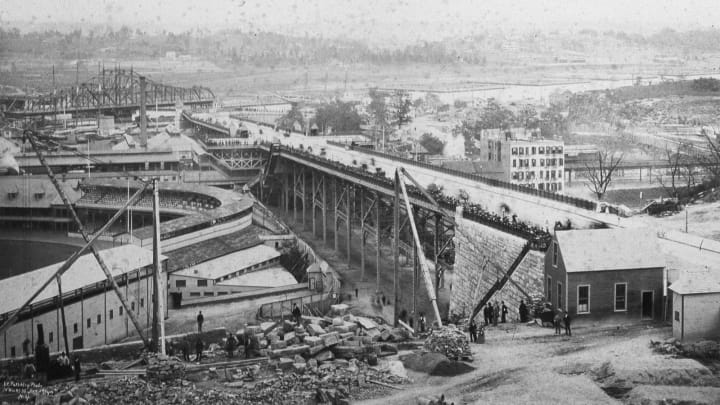

In October and through the start of November, it appeared as though we were on a collision course for the Thanksgiving Day game between Yale and Princeton at the Polo Grounds to feature as a national championship tilt. Princeton defeated a team of school alumni before dispatching Rutgers and Penn in October, while Yale prevailed against Wesleyan and twice against Rutgers.

Entering the heart of the season, the Tigers secured a pair of wins against Columbia and knocked off Penn and Rutgers a second time. They could not, however, handle a Harvard team determined to prevail in front of a home crowd of around 1,200 spectators at Holmes Field in Cambridge. While a lot changed in college football over the years, one thing that was already well entrenched was ire for referees, as several controversial calls in both directions marked this contest.

Harvard walked away 2-1 victors, and as a result it was the Crimson rather than the Tigers who set themselves up for a championship tilt with Yale. Up to that point, Harvard had defeated MIT twice along with McGill, Amherst, Dartmouth, Columbia, and a team selected from among Harvard alumni. As they prepared to host their rivals in The Game, the Crimson boasted a perfect 8-0 record and were confident that they could defeat the Bulldogs for the first time since their inaugural meeting in 1875.

The Bulldogs, however, had different ideas. After winning their three games in October, the Elis went on to dispatch MIT, Amherst, and Columbia before their showdown with Harvard.

Yale did not overlook their rivals, wary of what they had done to Princeton the week before. Around 10 percent of the crowd at Holmes Field was comprised of Bulldog partisans who traveled from New Haven to Cambridge for the contest, and there was a palpable tension in the chilly wind as the two teams squared off in the tensest contest either had yet faced in 1882.

Yale walked away victorious after scoring an early goal off the boot of Eugene Lamb Richards and then hanging on for dear life as Harvard threatened to tie up the contest. It created plenty of cause for celebration, but while Harvard’s season was complete after the Yale game the Bulldogs still had to travel to New York to square off against Princeton on Thanksgiving.

Despite their loss to Harvard, Princeton could still throw a wrench in the national championship picture with a win at the Polo Grounds. A Tigers victory would put Harvard, Yale, and Princeton all 1-1 against each other and undefeated in every other contest that season.

Just as was the case against Harvard, however, Yale found a way to maintain their perfect record. In front of a crowd of around 7,000 spectators in New York, the Bulldogs locked down the title.

Richards kicked two goals from touchdown for the Bulldogs, as they finished the season as the only undefeated team in the land. Princeton managed to halve the deficit on a goal from open play late in the game, as Haxall booted a daring kick from what was estimated to be nearly 40 yards from goal. The Tigers, though, could not find an equalizing score and were forced to settle for third wheel behind their two main rivals.

Nobody could dispute that Yale was the best team of 1882. What they didn’t know yet at the time, though, was that the Bulldogs were only just getting started.